Learning Beyond School Walls in Times of Inequality

-

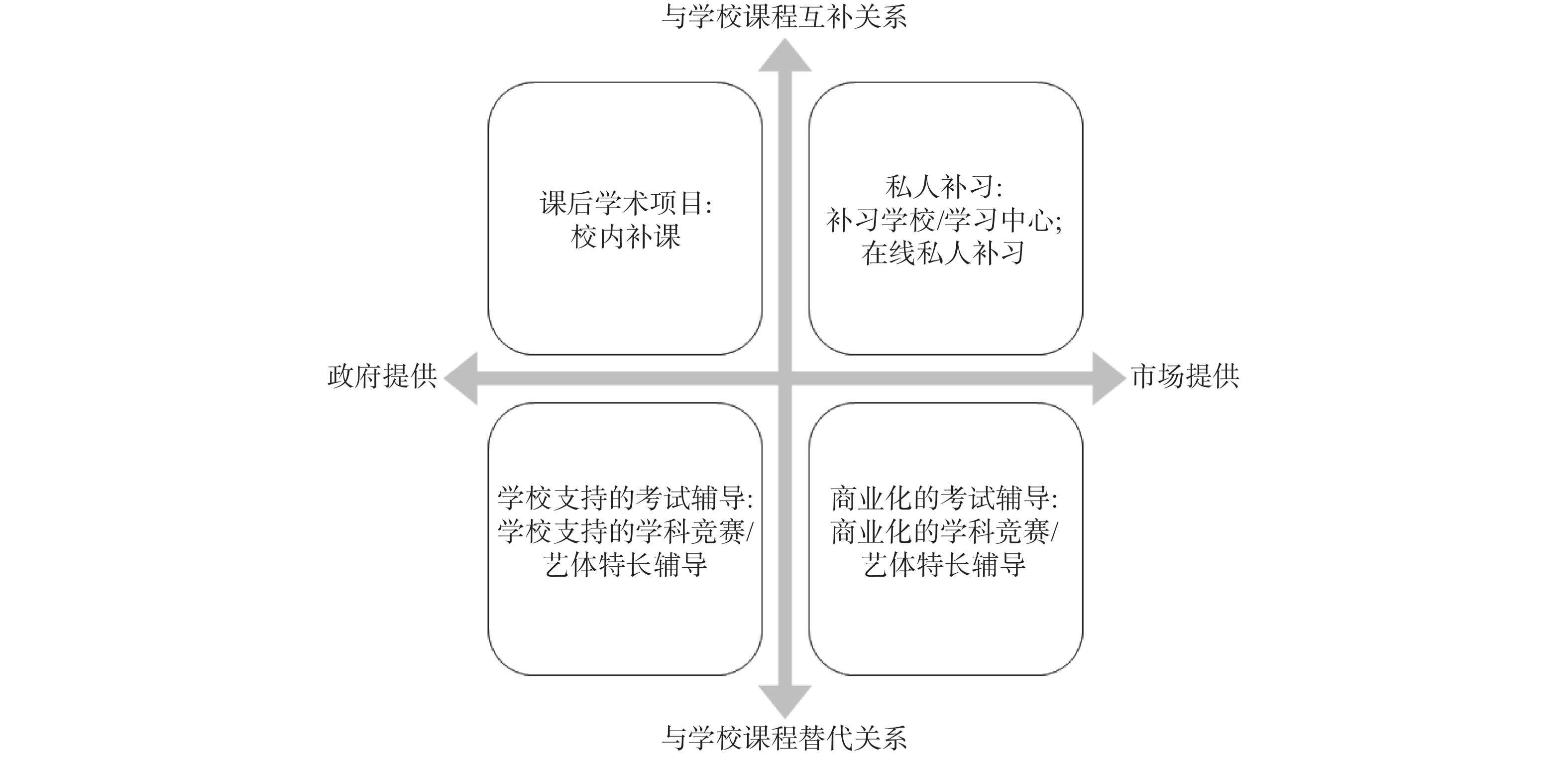

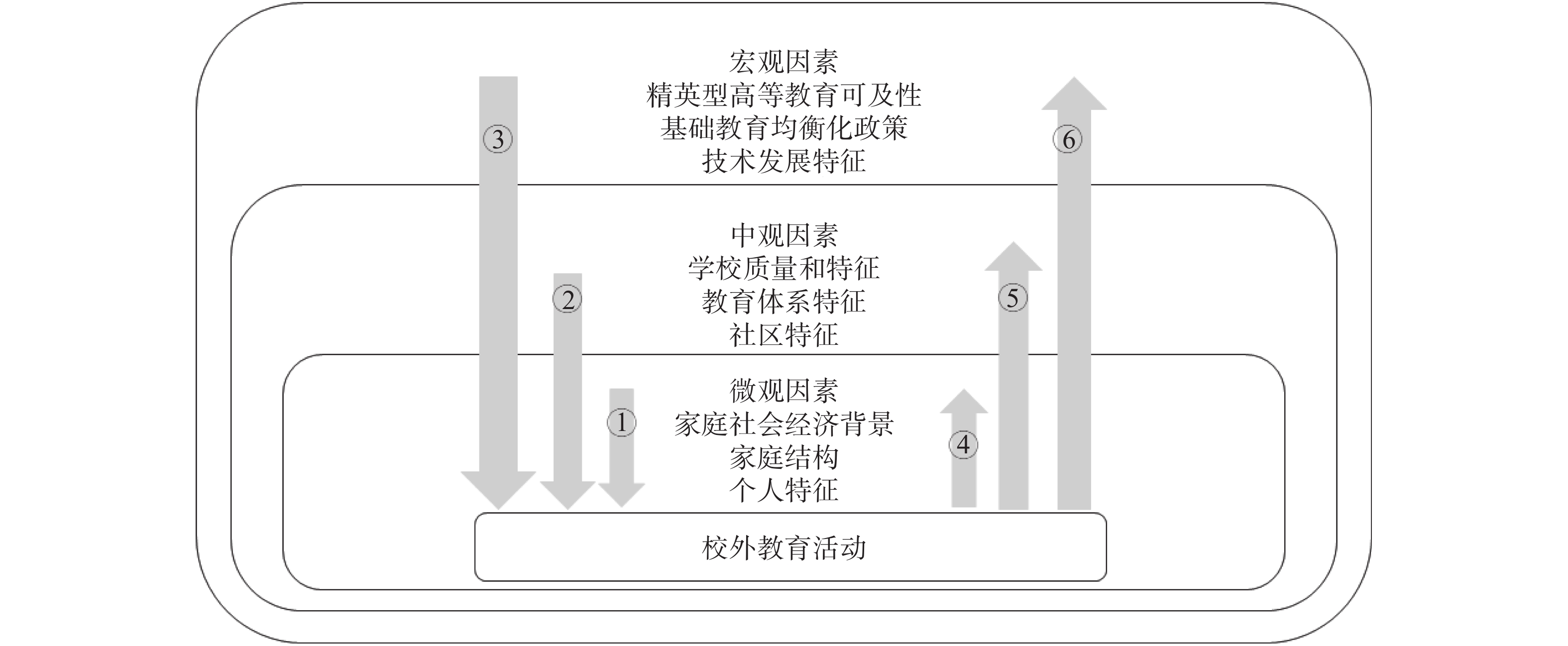

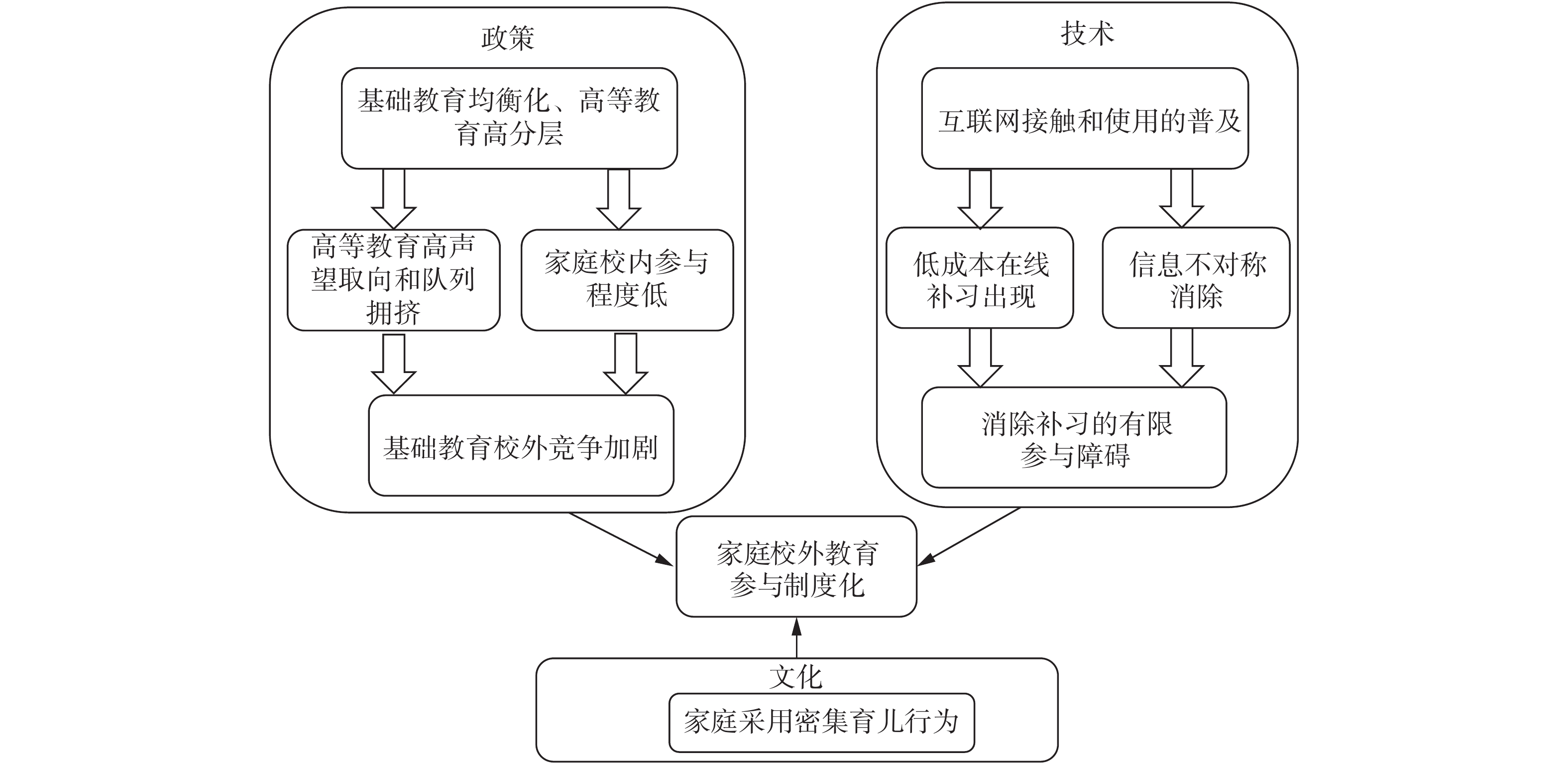

摘要: 在经济不平等、基础教育均衡化和“互联网+教育”并行发展的背景下,校外补习进入新阶段,其特征是广泛参与和深入参与。校外补习逐步发展为政府和市场共同提供的校外教育活动,这些活动受到微观、中观和宏观三个层次因素的影响。当前校外教育领域出现三大趋势:一是基础教育均衡化政策和高等教育的分层发展战略促使基础教育竞争从校内转向校外;二是经济不平等的环境中,父母加大了对校外教育的参与,密集化育儿文化出现并广为扩散;三是互联网等技术的普及消除了校外补习的有限参与障碍,拓宽了家庭教育选择的范围。政策—文化—技术的互动促使家庭的校外教育活动参与日趋制度化。其后果是基础教育从“高校内竞争、低校外竞争,低补习参与”的低水平均衡转化为“低校内竞争、高校外竞争、高补习参与”的高水平均衡。在后补习时代,校外教育活动逐步成为社会分层与流动的主要工具。政府应调整对校外教育的认识,承担起弥合校外教育参与的阶层差异的责任。Abstract: Against the background of the parallel development of economic inequality, equalization of compulsory education, and growth of online technology, private tutoring enters a new era, characterized by extensive and intensive household participation. It has gradually transformed into a new form of out-of-school learning, provided by the government and the market. Such learning activities are governed by micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors. There are three new trends in this field. First, the equalization policy for basic education and the stratification strategy for tertiary education have jointly pushed the basic education competition out of the school wall. Second, income inequality forces parents to increase their time and financial inputs, and thus the intensive parenting spreads out globally. Third, internet technology removes household’s barriers to participate in after-school learning, and increase their choice. The interactions among the policy, the culture, and the technology facilitate the institutionalization of learning beyond school walls. One significant consequence of such transformation is that the low-level equilibrium, characterized by high within school competition, low outside-school competition, and low-level private tutoring, is replaced by a new high-level equilibrium, characterized by low within school competition, high outside-school competition, and high-level private tutoring. In the post-tutoring era, learning beyond school walls is turning into a major instrument for social mobility and stratification. As such, the government needs to adjust its understanding and take the responsibility of closing the class divide in out-of-school learning opportunities.

-

Key words:

- out-of-school learning /

- institutionalization /

- income inequality

1) ①作者感谢匿名审稿人提出的意见。为特殊学生群体提供的教学服务属于学校正规教育的组成部分,根据全纳教育原则,很多公办学校为此类儿童提供校内教育机会。但是,本文强调的是有部分学校将此类服务外包给社会组织(如公益组织或者培训机构),也有学校将部分服务外包给社会组织,这些服务属于校外教育活动。2) ②在实证分析中,研究者常采用父母育儿参与度问题来衡量教养方式强度,例如将父母每周至少讨论一次孩子在学校的表现、每周至少与孩子交谈一次、每周至少与孩子一起吃一顿饭定义为密集型育儿(德普克和齐利博蒂,2019)。 -

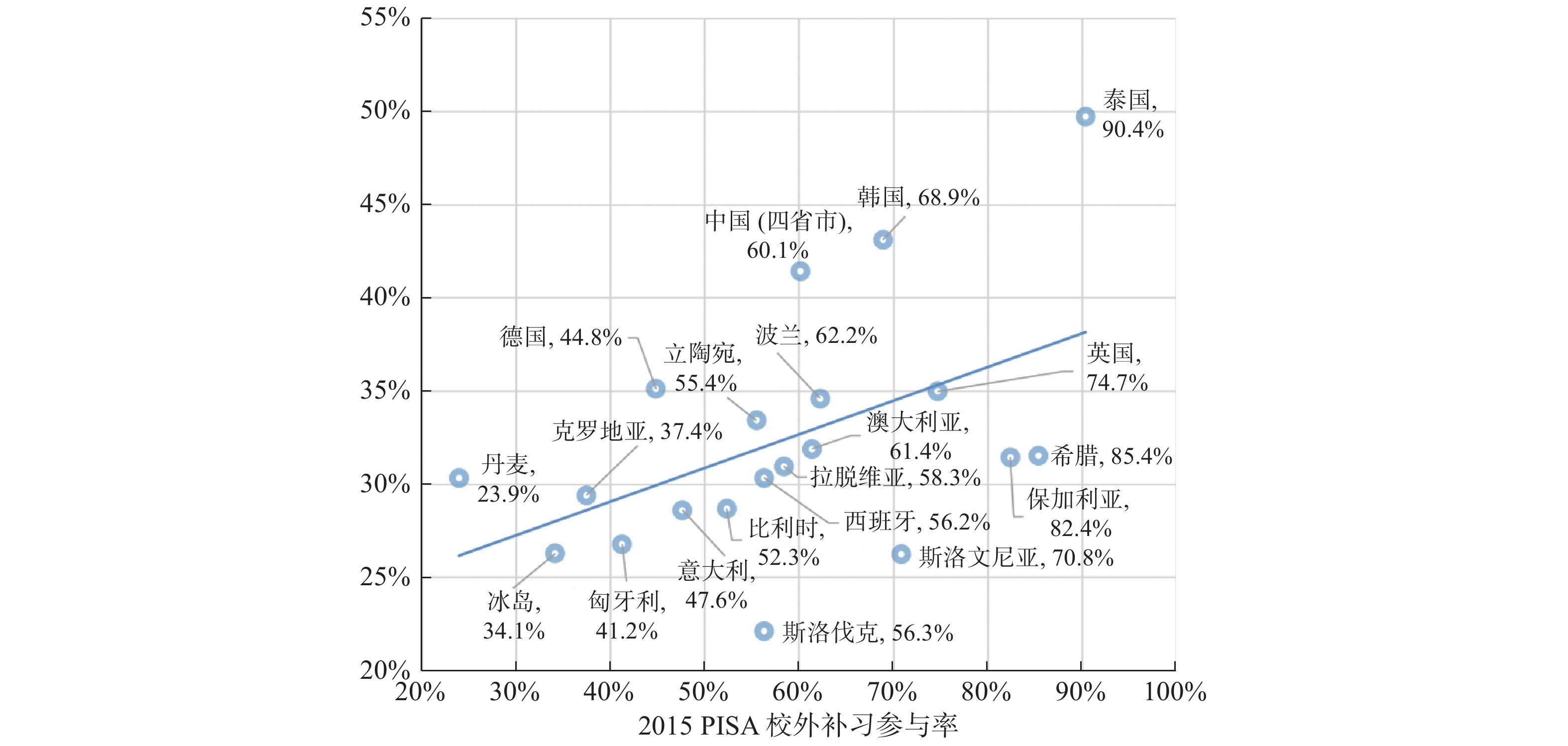

表 1 2003—2015年PISA历年15岁学生补习参与率

国家/地区 15岁学生补习参与情况 2003年 2012年 2015年 澳大利亚 16.7% 19.2% 61.35% 比利时 7.4% 16.7% 52.29% 中国(四省市) n.a. n.a. 60.15% 保加利亚 n.a. n.a. 82.37% 克罗地亚 n.a. n.a. 37.41% 丹麦 4.3% 6.6% 23.90% 德国 22.1% 20.6% 44.82% 希腊 45.0% 51.4% 85.38% 香港 22.4% 27.0% 58.71% 匈牙利 25.2% 41.6% 41.23% 冰岛 17.2% 18.9% 34.13% 意大利 20.3% 32.9% 47.62% 韩国 25.0% 31.0% 68.90% 拉脱维亚 21.5% 28.5% 58.35% 立陶宛 n.a. n.a. 55.45% 秘鲁 n.a. n.a. 63.62% 波兰 17.9% 42.1% 62.22% 斯洛伐克 20.9% 22.8% 56.28% 斯洛文尼亚 n.a. n.a. 70.80% 西班牙 32.3% 41.6% 56.25% 西班牙(地区) n.a. n.a. 55.99% 泰国 19.9% 50.3% 90.36% 英国 12.2% 18.4% 74.68% 均值 20.6% 29.4% 63.89% 数据来源:2003年和2012年PISA补习率数据为任意学科校外补习的参与率,数据来源于Park,Buchmann,Choi et al.(2016),Table1,p.233;2015年数据来自于the Program for International Student Assessment 2015;作者根据相应数据计算。

注释:①中国(四省市)是指:北京、上海、江苏和广东 ②n.a.表示数据不可得。 -

[1] 安妮特•拉鲁. (2010). 不平等的童年(张旭译). 北京: 北京大学出版社. [2] 杜凤莲, 王文斌, 董晓媛. (2018). 时间都去哪儿了? 中国时间利用调查研究报告. 中国社会科学出版社. [3] 甘犁, 尹志超, 贾男, 徐舒, 马双. (2013). 中国家庭资产状况及住房需求分析. 金融研究,(4),1−14. [4] 胡咏梅, 范文凤, 丁维莉. (2015). 影子教育是否扩大教育结果的不均等——基于PISA2012上海数据的经验研究. 北京大学教育评论,(3),35−52+194. [5] 黄春寒. (2019). 基础教育阶段家庭教育支出现状, 魏易主编(2019)中国教育财政家庭调查报告, 67—87页. 社会科学文献出版社, 2019. [6] 李春玲. (2014). 教育不平等的年代变化趋势(1940—2010)——对城乡教育机会不平等的再考察. 社会学研究,(2),65−89. [7] 李建新, 任强, 吴琼. (2015). 中国民生发展报告. 北京大学出版社. [8] 李培林, 戈尔什科夫, (2018). 中国和俄罗斯的中等收入群体: 影响和趋势. 社会科学文献出版社. [9] 马春华. (2018). 中国家庭儿童养育成本及其政策意涵. 妇女研究论丛,(5),70−84. [10] 马赛厄斯•德普克, 法布里奇奥•齐利博蒂. (2019). 爱、金钱和孩子: 育儿经济学. 格致出版社. [11] 宋映泉. (2012). 民办学前教育规模占比的省际差异、政府财政投入与管制. 北京大学教育评论,10(2),97−119. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-9468.2012.02.007 [12] 魏建国, 罗朴尚, 宋映泉. (2011). 高中学生对大学成本和学生资助信息的知晓状况分析——基于对我国西部41个贫困县的调研. 教育发展研究,(21),7−13. [13] 薛海平. (2016). 课外补习、学习成绩与社会再生产. 教育与经济,(2),32−43. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-4870.2016.02.005 [14] 杨钋, 徐颖. (2017). 数字鸿沟与家庭教育投资不平等. 北京大学教育评论,15(4),126−154. [15] 俞可. (2011). 教育, 走进战国时代?——漫话《虎妈战歌》. 北京大学教育评论,(2),168−176. [16] Altintas, Evrim. (2016). The Widening Education Gap in Developmental Child Care Activities in the United States, 1965—2013. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 26−42. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12254 [17] Aurini, J., & Davies, S. (2004). The transformation of private tutoring: Education in a franchise form. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 29(3), 419−438. [18] Baker, D. P. (2009). The educational transformation of work: towards a new synthesis. Journal of Education & Work, 22(3), 163−191. [19] Baker, D. P., Akiba, M., LeTendre, G. K. & Wiseman, A. W. (2001). Worldwide shadow education: Outside-school learning, institutional quality of schooling, and cross-national mathematic achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(1), 1−17. doi: 10.3102/01623737023001001 [20] Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887−907. doi: 10.2307/1126611 [21] Bound, J., & Turner, S. (2006). Cohort crowding: How resources affect collegiate attainment. Journal of Public Economics, 91(5), 877−899. [22] Bray, M. (1999). The shadow education system: Private tutoring and its implications for planners. Fundamentals of Educational Planning No. 61. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. [23] Bray, M. (2009). Confronting the Shadow Education System: What Government Policies for What Private Tutoring? Paris: UNESCO/ International Institute for Educational Planning. [24] Buchmann, C., Condron, D. J., & Roscigno, V. J. (2010). Shadow education, American style: Test preparation, the SAT and college enrollment. Social Forces, 89(2), 435−461. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0105 [25] Burch P, Steinberg, M, & Donovan J. (2007). Supplemental educational services and NCLB: Policy assumptions, market practices, emerging issues. Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 29(2), 115−33. doi: 10.3102/0162373707302035 [26] Byun, S. (2010). Does policy matter in shadow education spending? Revisiting the effects of the high school equalization policy in South Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(1), 83−96. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9061-9 [27] Cooper, M. (2014). Cut Adrift: Families in Insecure Times. Berkeley: University of California Press. [28] Dang, H. A. (2007). The determinants and impact of private tutoring classes in Vietnam. Economics of Education Review, 26(6), 683−98. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.10.003 [29] Dang, H. A., & Rogers, F. H. (2008). The growing phenomenon of private tutoring: Does it deepen human capital, widen inequalities, or waste resources?. The World Bank Research Observer, 23(2), 161−200. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkn004 [30] Davies, S. (2004). School choice by default? Understanding the demand for private tutoring in Canada. American Journal of Education, 110(3), 233−255. doi: 10.1086/383073 [31] Duncan, G. & Murnane, R. (2011). Introduction: The American Dream, Then and Now. In Duncan, G. J. and Murnane, R., (eds.) Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, USA, pp. 3−25. [32] GoldFarb, A., & Tucker, C. (2019). Digital Economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(1), 3−43. doi: 10.1257/jel.20171452 [33] Goldin, C. & Katz, L. F. (2010). The Race Between Education and Technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [34] Grodsky E, Warren J .R, & Felts E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 385−404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134711 [35] Guryan, Jonathan, Erik Hurst, and Melissa Kearney. (2008). Parental Education and Parental Time with Children. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 23−46. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.3.23 [36] Hastings, J. S., & Weinstein, J. M. (2008). Information, school choice, and academic achievement: Evidence from two experiments. The Quarterly journal of economics, 123(4), 1373−1414. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2008.123.4.1373 [37] Hoxby, C. M. (2009). The Changing Selectivity of American Colleges. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(4), 95−118. doi: 10.1257/jep.23.4.95 [38] Jensen, R. (2010). The perceived returns to education and the demand for schooling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 515−548. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2010.125.2.515 [39] Jung, J. H, & Lee, K. H. (2010). The determinants of private tutoring participation and attendant expenditures in Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(2), 159−68. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9055-7 [40] Kaushal, Neeraj, Magnuson, Katherine and Waldfogel, Jane. (2011) How is family income related to investments in children’s learning? In Duncan, Greg J. and Murnane, Richard, (eds.) Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children's Life Chances. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, USA, pp. 187−206. [41] Kim, J.H, & Park, D. (2010). The determinants of demand for private tutoring in South Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(3), 411−21. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9067-3 [42] Kornrich, S., & Furstenberg, F. (2013). Investing in children: changes in parental spending on children, 1972—2007. Demography, 50(1), 1−23. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0146-4 [43] Kornrich, Sabino. (2016). Inequalities in Parental Spending on Young Children: 1972 to 2010. AERA Open, (2), 1−12. [44] Lauer P.A, Akiba. M, Wilkerson SB, Apthorp HS, Snow D, & Martin-Glenn ML. (2006). Out-of-school-time programs: a meta-analysis of effects for at-risk students. Review of Education Research, 76(2), 275−313. doi: 10.3102/00346543076002275 [45] Lavy V, & Schlosser A. (2005). Targeted remedial education for underperforming teenagers: costs and benefits. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 839−74. doi: 10.1086/491609 [46] Lee, J. & Shouse, L. R. C. (2011). The impact of prestige orientation on shadow education in South Korea. Sociology of Education, 84(3), 212−224. doi: 10.1177/0038040711411278 [47] Lee, C.J, Lee H, & Jang H-M. (2010). The history of policy responses to shadow education in South Korea: implications for the next cycle of policy responses. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(1), 97−108. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9064-6 [48] Lee, J. (2007). Two worlds of private tutoring: The prevalence and causes of after-school mathematics tutoring in Korea and the United States. Teachers College Record, 109(5), 1207−1234. [49] Loyalka, P., Song, Y.Q., Wei, J.G., Zhong, W.P., & Rozelle, S. (2013). Information, college decisions and financial aid: Evidence from a cluster-randomized controlled trial in china. Economics of Education Review, 36, 26−40. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.05.001 [50] Lubienski C, & Lee J. (2013). Making markets: policy construction of supplementary education in the United States and Korea. In J Aurini, S Davies, J Dierkes, (eds) Out of the Shadows: The Global Intensification of Supplementary Education. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group. pp. 223−44. [51] Lynch K, & Moran, M. (2006). Markets, schools, and the convertibility of economic capital: the complex dynamics of class choice. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 27(2), 221−35. doi: 10.1080/01425690600556362 [52] Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.) & E. M. Hetherington (eds), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed). New York: Wiley. pp. 1−101. [53] Machin S, McNally S, & Meghir C. (2004). Improving pupil performance in English secondary schools: excellence in cities. Journal of European Economics Association, 2(2−3), 396−405. doi: 10.1162/154247604323068087 [54] Marginson, S. (2016). High participation systems of higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 243−271. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2016.0007 [55] Mori, I., & Baker, D. (2010). The origin of universal shadow education: What the supplemental education phenomenon tells us about the postmodern institution of education. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(1), 36−48. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9057-5 [56] Nguyen, T. (2008) Information, Role Models and Perceived Returns to Education: Experimental Evidence from Madagascar, MIT Working Paper. [57] Novokmet, F., Piketty, T., & Zucman, G. (2017). From soviets to oligarchs: inequality and property in Russia 1905—2016. Journal of Economic Inequality, 16(2), 1−35. [58] Park, H., Buchmann, C., Choi, J., & Merry, J. J. (2016). Learning Beyond the School Walls: Trends and Implications. Review of Sociology, 42(1), 231−252. [59] Park, H., Byun, S. Y., & Kim, K. K. (2011). Parental involvement and students’ cognitive outcomes in Korea: Focusing on private tutoring. Sociology of Education, 84(1), 3−22. doi: 10.1177/0038040710392719 [60] Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century: A multidimensional approach to the history of capital and social classes. British Journal of Sociology, 65(4), 736−747. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12115 [61] Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2003). Income inequality in the united states, 1913—1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 1−39. doi: 10.1162/00335530360535135 [62] Piketty, T., & Zucman, G. (2014). Capital is back: Wealth-income ratios in rich countries 1700—2010. Cepr Discussion Papers, 129(3), 1255−1310. [63] Piketty, T., Yang, L., & Zucman, G. (2017). Capital accumulation, private property and rising inequality in China, 1978-2015. Cepr Discussion Papers. [64] Ramey, G., & Ramey, V. A. (2010). The rug rat race. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2010(1), 129−199. doi: 10.1353/eca.2010.0003 [65] Safarzynska K. (2011). Socio-economic determinants of demand for private tutoring. European Sociology Review, 15, 1−16. [66] Schneider, D., Hastings, O. P., & Labriola, J. (2018). Income Inequality and Class Divides in Parental Investments. American Sociological Review, 83(3), 475−507. doi: 10.1177/0003122418772034 [67] Schneider, M., & Buckley, J. (2002). What do parents want from schools? Evidence from the internet. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2), 133−144. doi: 10.3102/01623737024002133 [68] Schneider, M., Marschall, M., Teske, P., & Roch, C. (1998). School choice and culture wars in the classroom: What different parents seek from education?. Social Science Quarterly, 79(3), 489−501. [69] Seth, Michael J. (2002). Education Fever: Society, Politics, and the Pursuit of Schooling in South Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii. [70] Stevenson D, L, Baker D, P. (1992). Shadow education and allocation in formal schooling: Transition to university in Japan. American Journal of Sociology, 97(6), 1639−1657. [71] Tansel A, & Bircan F. (2006). Demand for education in Turkey: A Tobit analysis of private tutoring expenditures. Economics of Education Review, 25(3), 303−13. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.02.003 [72] Yang, P. & Wang, R. (2020). Central-local relations and higher education stratification in China. Higher Education, 79, 111−139. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00399-z [73] York, B. & Loeb, S. (2014) One Step at a Time: The Effects of an Early Literacy Text Messaging Program for Parents of Preschoolers. NBER Working Paper 20659. [74] Zhang, W., & Bray, M. (2015). Shadow education in Chongqing, China: Factors underlying demand and policy implications. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 12(1), 83−106. [75] Zhang, Y., & Xie, Y. (2016). Family background, private tutoring, and children’s educational performance in contemporary China. Chinese sociological review, 48(1), 64−82. doi: 10.1080/21620555.2015.1096193 -

下载:

下载: