The Participation in Shadow Education of Adolescents: School Peer Group and Ascribed Difference——A Multilevel Analysis Based on CEPS Data

-

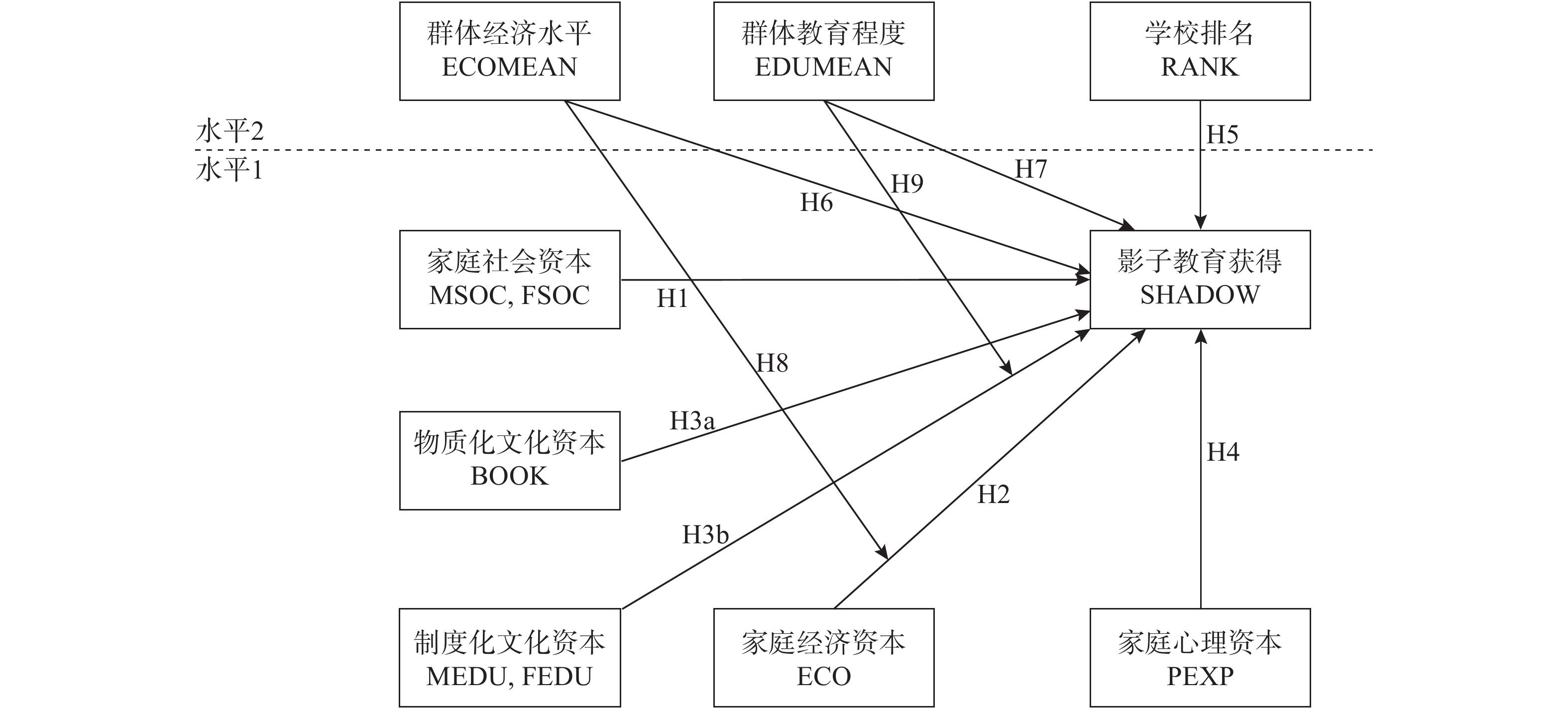

摘要: 青少年影子教育的影响因素及其作用机制是现有研究尚未充分讨论的问题。本研究使用“中国教育追踪调查”(CEPS)基线数据进行多水平分析的结果显示,青少年影子教育参与机会受到先赋因素和学校群体因素的双重影响。在影子教育参与机会的差异中,有超过40%的方差是来自学校层面,并且学校因素主要通过同伴效应对影子教育参与产生作用。除直接影响外,同伴群体因素还通过调节效应间接影响先赋因素的作用强度。进一步的分析发现,不同类型的影子教育受到不同先赋因素的影响。其中,学术类的影子教育主要受到家庭社会资本和经济资本的影响,而才艺类影子教育主要受到家庭文化资本的影响。Abstract: The influence factors and their impact on shadow education opportunities are not fully discussed in existing studies. Applying China Education Panel Survey data and multilevel analysis model, we find that adolescents’ shadow education is influenced by family background and school peer group factors. More than 40% of the variance comes from the school level, and the school factors play a role in shadow education mainly through peer effect. In addition to the direct impact, peer group factors also indirectly affect the role of ascribed factors by moderation effect. In the subdivision, different types of shadow education are affected by different ascribed factors. The academic type is mainly influenced by the social capital and economic capital of the family, while the talent type is mainly influenced by the cultural capital of the family. These findings can provide a reference for further understanding of the behavior of family education investment and the role of shadow education in social reproduction function.

-

Key words:

- shadow education /

- school peer group /

- CEPS /

- multilevel logit model

1) ① 具体请参见《中国教育追踪调查(CEPS)基线数据使用手册》。2) ② 相应编码为:“无业、失业、下岗”=1;“农民”=2;“个体户”=3;“商业与服务业一般职工”=4;“生产与制造业一般职工”=5;“技术工人”=6;“教师、工程师、医生、律师”=7;“企业公司中的高管人员”=8;“国家机关事业单位领导与工作人员”=9。3) ③ 相应编码为:“现在就不要念了”=6;“初中毕业”=9;“中专/技校”=10;“职业高中”=11;“普通高中”=12;“大学专科”=15;“大学本科”=16;“研究生”=19;“博士”=23。 -

表 1 数据的描述性统计

变量名称 变量代码 水平 样本量 均值 标准差 最小值 最大值 性别 SEX 1 14929 0.50 0.50 0.00 1.00 年级 GRADE 1 14929 0.47 0.50 0.00 1.00 户籍 HK 1 14929 0.44 0.50 0.00 1.00 认知能力 COG 1 14929 0.05 0.85 −2.03 2.71 母亲职业地位 MSOC 1 14929 4.03 2.24 1.00 9.00 父亲职业地位 FSOC 1 14929 4.77 2.41 1.00 9.00 家庭经济资本 ECO 1 14929 2.82 0.59 1.00 5.00 家庭藏书量 BOOK 1 14929 3.19 1.20 1.00 5.00 母亲教育程度 MEDU 1 14929 9.48 3.47 0.00 20.00 父亲教育程度 FEDU 1 14929 10.24 3.12 0.00 20.00 家庭教育期望 PEXP 1 14929 17.13 3.57 6.00 23.00 学校排名 RANK 2 112 3.88 0.82 1.00 5.00 群体经济水平 ECOMEAN 2 112 2.83 0.23 2.09 3.23 群体教育程度 EDUMEAN 2 112 9.83 1.89 5.68 15.37 表 2 青少年影子教育参与的多水平分析结果

因变量: 是/否 学术类/否 才艺类/否 通识类/否 SHADOW (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 固定影响 MSOC 0.008 0.013 0.015 0.008 0.003 0.030 (0.010) (0.011) (0.010) (0.015) (0.023) (0.014)** FSOC 0.025 0.031 0.030 0.037 0.008 0.040 (0.010)** (0.010)*** (0.010)*** (0.014)*** (0.022) (0.014)*** ECO 0.176 0.198 0.179 0.178 0.115 0.240 (0.037)*** (0.043)*** (0.044)*** (0.067)*** (0.098) (0.062)*** BOOK 0.110 0.122 0.117 0.028 0.273 0.192 (0.020)*** (0.022)*** (0.020)*** (0.030) (0.050)*** (0.030)*** MEDU 0.026 0.030 0.038 0.025 0.072 0.049 (0.008)*** (0.009)*** (0.010)*** (0.014)* (0.022)*** (0.013)*** FEDU 0.007 0.009 0.011 −0.013 0.041 0.026 (0.008) (0.009) (0.009) (0.013) (0.020)** (0.012)** PEXP 0.030 0.037 0.035 0.042 0.044 0.037 (0.006)*** (0.007)*** (0.006)*** (0.009)*** (0.015)*** (0.010)*** SEX −0.187 −0.225 −0.217 −0.071 −0.365 −0.370 (0.038)*** (0.042)*** (0.040)*** (0.058) (0.094)*** (0.056)*** HK 0.237 0.249 0.236 0.242 0.265 0.322 (0.047)*** (0.051)*** (0.048)*** (0.071)*** (0.112)** (0.070)*** GRADE 0.376 0.459 0.449 0.384 0.521 0.631 (0.038)*** (0.043)*** (0.041)*** (0.060)*** (0.095)*** (0.058)*** COG 0.029 0.026 0.027 0.111 −0.142 0.018 (0.025) (0.028) (0.027) (0.039)*** (0.060)** (0.038) RANK −0.247 −0.239 −0.332 −0.186 −0.213 (0.104)** (0.103)** (0.135)** (0.095)* (0.112)* ECOMEAN 1.828 1.951 3.410 1.471 1.814 (0.542)*** (0.527)*** (0.721)*** (0.527)*** (0.584)*** EDUMEAN 0.385 0.411 0.457 0.330 0.465 (0.065)*** (0.064)*** (0.084)*** (0.062)*** (0.070)*** ECOMEAN*ECO 0.273 0.506 −0.752 0.675 (0.200) (0.351) (0.452) (0.288)** EDUMEAN*MEDU −0.010 −0.014 −0.031 −0.007 (0.004)** (0.006)** (0.009)*** (0.006) 常数项 −2.651 −11.055 −1.208 −1.690 −4.686 −2.620 (0.234)*** (1.169)*** (0.439)*** (0.585)*** (0.546)*** (0.501)*** 随机影响 组间方差 1.815 0.803 0.644 0.659 0.659 0.659 χ2 (3042.41)*** (1363.10)*** (1352.18)*** (855.3)*** (855.3)*** (855.3)*** Deviance 13063.72 12970.25 12939.26 39722.28 39722.28 39722.28 注:表中系数为logit单位;“*”“**”“***”分别表示在10%、5%、1%的水平显著。 -

[1] 鲍尔斯, 金蒂斯. (1990). 美国: 经济生活与教育改革(王佩雄译). 上海: 上海译文出版社. [2] 范兴华, 余思, 彭佳, 方晓义. (2017). 留守儿童生活压力与孤独感、幸福感的关系: 心理资本的中介与调节作用. 心理科学,40(02),388−394. [3] 李春玲. (2003). 社会政治变迁与教育机会不平等——家庭背景及制度因素对教育获得的影响(1940—2001). 国社会科学, (03),86−98. [4] 李佳丽, 胡咏梅. (2017). 谁从影子教育中获益? 兼论影子教育对教育结果均等化的影响. 教育与经济, (02),51−61. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-4870.2017.02.007 [5] 李佳丽. (2016). 谁从影子教育中获益——基于选择假说和理性选择理论. 教育发展研究,36(20),66−73. [6] 刘录护, 扈中平. (2012). 个人教育获得: 学校取代抑或延续了家庭的影响——两种理论视野的比较. 华南师范大学学报(社会科学版), (01),21−28. [7] 彭湃, 胡咏梅, 埃克哈德·克里默. (2015). 学校增值的一致性与稳定性——基于多水平追踪数据的实证研究. 教育研究,36(07),73−80. [8] 王晓磊. (2017). 初中阶段教育质量与影子教育机会的不平等——以CEPS 2013—2014数据为例. 北京社会科学, (09),50−60. [9] 薛海平, 丁小浩. (2009). 中国城镇学生教育补习研究. 教育研究, (01),39−46. [10] 薛海平, 李静. (2016). 家庭资本、影子教育与社会再生产. 教育经济评论,1(04),60−81. [11] 薛海平. (2015). 从学校教育到影子教育: 教育竞争与社会再生产. 北京大学教育评论,13(03),47−69. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-9468.2015.03.004 [12] Abdulkadiroglu, A., Angrist, J., & Pathak, P. (2014). The elite illusion: Achievement effects at Boston and New York exam schools. Econometrica, 82(1), 137−196. doi: 10.3982/ECTA10266 [13] Bernstein, B. (1977). Class, Codes and Control: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [14] Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In: Brown, R.: Knowledge, Education, and Cultural Change(pp.71−112). London: Tavistock. [15] Bray, M., & Kwok, P. (2013). Demand for private supplementary tutoring: Conceptual considerations and socio-economic patterns in Hong Kong. Economics of Education Review, (22), 611−620. [16] Bray, M., Zhan, S., Lykins, C., Wang, D., & Kwo, O. (2014). Differentiated demand for private supplementary tutoring: Patterns and implications in Hong Kong secondary education. Economics of Education Review, 38, 24−37. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.10.002 [17] Bray, M. (1999). The Shadow Education System: Private Tutoring and Its Implications for Planners. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. [18] Bray, M. (2009). Confronting the Shadow Education System: What Government Policies for What Private Tutoring? Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. [19] Bray, M. (2013). Benefits and tensions of shadow education: Comparative perspectives on the roles and impact of private supplementary tutoring in the lives of Hong Kong students’. Journal of International and Comparative Education, 2(1), 18−30. doi: 10.14425/00.45.72 [20] Bray, M., Kobakhidze, M. N., Zhang, W. & Liu, J. (2018). The hidden curriculum in a hidden marketplace: Relationships and values in Cambodia’s shadow education system. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(4), 435−455. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2018.1461932 [21] Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [22] Büchner, C., Cörvers, F., & Traag, T. (2012). How do education, cognitive skills, cultural and social capital account for intergenerational earnings persistence? Evidence from the Netherlands. Social Science Electronic Publishing, (7), 1−29. [23] Caldas, S. J., & Bankston, C. (1997). Effect of school population socioeconomic status on individual academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(5), 269−277. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1997.10544583 [24] Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, (94), 95−120. [25] Crosnoe, R. (2009). Low-income students and the socioeconomic composition of public high schools. American Sociological Review, 74(5), 709−730. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400502 [26] Ding, W., & Lehrer, S. F. (2007). Do peers affect student achievement in China's secondary schools?. Review of Economics & Statistics, 89(2), 300−312. [27] Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 189−214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412 [28] Entrich, S. R. (2015). The decision for shadow education in Japan: Students’ choice or parents’ pressure?. Social Science Japan Journal, 18(2), 193−216. doi: 10.1093/ssjj/jyv012 [29] Ghosh, P., & Mark, B. (2018). Credentialism and demand for private supplementary tutoring: A comparative study of students following two examination boards in India. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 20(1), 33−50. doi: 10.1108/IJCED-10-2017-0029 [30] Hauser, R. M., & Sewell, W. H. (1986). Family effects in simple models of education, occupational status and earnings: Finding from the Wisconsin and Kalamazoo studies. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3), 83−115. doi: 10.1086/298122 [31] Jheng, Y. (2015). The influence of private tutoring on middle-class students’ use of in-class time in formal schools in Taiwan. International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 1−8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.11.019 [32] Kwok, P. (2010). Demand intensity, market parameters and policy responses towards demand and supply of private supplementary tutoring in China. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(1), 49−58. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9060-x [33] Li, C. (2013). The heterogeneous composition and multiple identities of China's middle class. In:M. K. Gorshkov, C. Scalon, & P. L. Li (ed). Handbook on social stratification in the BRIC countries: Change and perspective(pp.395—417). Singapore : World Scientific Publishing Company. [34] Liu, J. & Bray, M. (2017). Determinants of demand for private supplementary tutoring in China: Findings from a national survey. Education Economics, 25(2), 205−218. doi: 10.1080/09645292.2016.1182623 [35] Liu, J. (2019). A structural equation modeling analysis of parental factors underlying the demand for private supplementary tutoring in China. ECNU Review of Education, 2(1), 7−24. doi: 10.1177/2096531119840856 [36] Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642−1690. doi: 10.1086/321300 [37] Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33(2), 143−160. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.01.003 [38] Luthans, F., Avev, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541−572. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x [39] Raftery, A. E., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform, and opportunity in Irish education. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41−62. doi: 10.2307/2112784 [40] Smyth, E. (2009). Buying your way into college? Private tuition and the transition to higher education in Ireland. Oxford Review of Education, 35(1), 1−22. doi: 10.1080/03054980801981426 [41] Tansel, A., & Bircan, F. (2006). Demand for education in Turkey: A Tobit analysis of private tutoring expenditures. Economics of Education Review, 25(3), 162−171. [42] Teachman, D. J. (1987). Family background, educational resource and educational attainment. American Sociological Review, (52), 548−557. [43] Thongphat, N. (2012). A survey of Thai student performance in mathematics and English: Evaluating the effect of supplementary tutoring. Procedia Economics and Finance, (2), 253−362. [44] Tomura, A, Ryōichi N, & Teruya O. (2011). Modern class society: Disparity and diversity. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. [45] Walsemann, K. M., Bell, B. A., & Maitra, D. (2011). The intersection of school racial composition and student race ethnicity on adolescent depressive and somatic symptoms. Social Science & Medicine, 72(11), 1873−1883. [46] Yung, K. W. (2019). Exploring the L2 selves of senior secondary students in English private tutoring in Hong Kong. System, 80, 120−33. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.11.003 [47] Zhang, Y., & Liu, J. (2016). The effectiveness of private tutoring in China with a focus on class-size. International Journal of Educational Development, 46, 35−42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.006 [48] Zhang, Y. (2013). Does private tutoring improve students’ National College Entrance Exam performance?—A case study from Jinan, China. Economics of Education Review, 32(1), 1−28. [49] Zhao, G. (2015). Can money ‘buy’ schooling achievement? Evidence from 19 Chinese cities. China Economic Review, 35, 83−104. -

下载:

下载: